📌 Key Takeaways

Payment terms you inherited years ago are quietly designing your cash flow—whether anyone designed them or not.

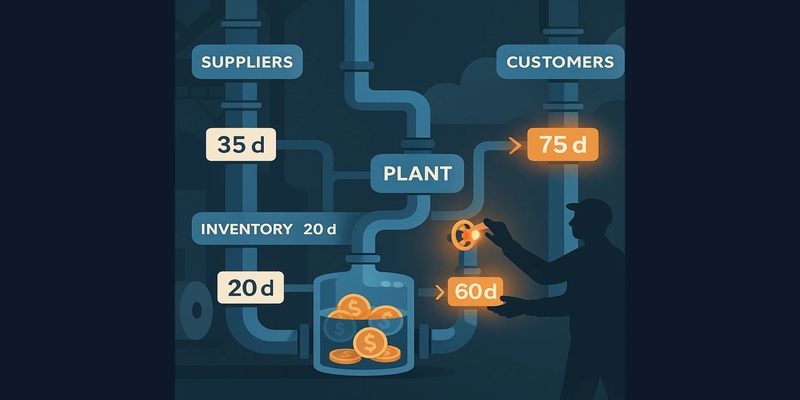

- The 40-Day Cash Trap: When suppliers demand payment in 35 days but customers actually pay in 75 days, you’re funding 40 days of operations out of your own pocket or overdraft, turning growth into a cash squeeze.

- Map Before You Negotiate: A simple three-column table showing on-paper terms versus actual payment timing for your top five suppliers and customers reveals exactly where cash gets stuck and which relationships deserve attention first.

- Small Shifts, Big Relief: Moving one major supplier from 35 to 45-day terms while tightening one large customer from 75 to 60 days can collapse a 40-day cash gap down to 15 days without burning any bridges.

- Stretch Is the Real Number: The difference between contractual payment terms (say, 60 days) and actual collection timing (often 75-80 days) is your “stretch,” and designing around reality instead of contracts prevents costly surprises.

- Three Scenarios Beat One Perfect Plan: Sketching a baseline, a stability-first scenario, and a stretch scenario lets you test which payment term adjustments actually reduce overdraft pressure before you start any negotiations.

Design payment terms intentionally, and growth stops feeling like suffocation. Small and mid-sized packaging converters juggling kraft paper suppliers and demanding customers will find a practical roadmap here, preparing them for the detailed playbook that follows.

Picture a mid-sized box plant. A major FMCG customer just awarded them a big contract. Volumes are up 25%. The team celebrates. Production ramps up. Kraft paper reels arrive daily.

Three months later, the overdraft is nearly maxed. A key kraft paper supplier is calling every day. The bank relationship manager is asking about limit breaches. Inside the plant, everyone is wondering: “How can we be busier than ever and still feel short of cash?”

Nothing dramatic changed—just one thing: the timing of cash leaving versus cash coming in. Suppliers commonly ask for 30 to 60-day payment terms. Customers—especially larger retailers and manufacturers—stretch to 60, 75, or even 90 days despite what the contract says, often skirting the spirit of prompt payment codes or local regulations intended to protect SMEs. Administrative delays, dispute resolutions, and fixed payment runs push actual cash receipt well beyond the agreed terms. This creates a structural mismatch that no amount of operational efficiency can solve.

This playbook provides a different approach to payment terms design for kraft paper suppliers and customers. You’ll learn how to map your current reality, understand the building blocks of payment terms on both sides, and create scenarios that align cash in and cash out. The goal isn’t perfect alignment—that’s rarely possible—but intentional design that reduces working capital strain and gives you more control. This guide is part of a broader learning journey on working capital and payment terms inside PaperIndex Academy.

Key Terms

Before diving into payment terms design, let’s clarify the core concepts:

Payment terms (credit days): The number of days a buyer has to pay after receiving goods or an invoice. “Net 45” means payment is due 45 days after the invoice date.

Cash conversion cycle: The number of days between when you pay suppliers and when customers pay you. A longer cycle means more cash is locked up in inventory and receivables. For readers seeking deeper background on this concept, Investopedia provides detailed explanations of how the cash conversion cycle connects to working capital management.

DSO (Days Sales Outstanding): The average number of days it takes to collect payment from customers after a sale. Lower DSO means faster cash collection.

DPO (Days Payable Outstanding): The average number of days you take to pay suppliers after receiving their invoice. Higher DPO means you hold onto cash longer.

Working capital limit / overdraft: A credit facility from your bank that covers short-term cash flow gaps. It’s meant for temporary mismatches, not structural problems.

Why Your Payment Terms Are Quietly Designing Your Cash Flow

Payment terms aren’t just administrative details buried in contracts. They determine when cash actually moves. A converter buying white kraft or brown packaging paper on 45-day terms and selling finished boxes on 75-day terms has a 30-day gap where cash is locked in operations. Scale that across all suppliers and customers, and you can easily have 60 to 90 days of cash tied up in the business—money that could otherwise reduce bank reliance or fund growth.

The challenge intensifies for small to mid-sized converters who lack negotiating power with kraft paper mills and large traders. In many standard domestic markets, suppliers typically structure terms in the 30 to 45-day range, though this varies significantly by region and market leverage. Meanwhile, customers—especially larger ones—may agree to pay in 60 days on paper, but administrative delays, dispute resolutions, or fixed payment runs frequently push actual cash receipt to 75 to 90 days or more.

Think of payment terms as plumbing. Inflow pipes (customer payments) and outflow pipes (supplier payments) need to be sized and timed so the tank never runs dry. Right now, most converters have outflow pipes that drain faster than inflow pipes can refill the tank. The bank overdraft becomes the emergency reserve, but it’s expensive and finite.

Here’s what typically happens: terms were set years ago based on what suppliers demanded and what customers would accept. Nobody revisited them as the business grew or as the customer mix changed. New suppliers get added with their standard terms. New customers negotiate harder payment terms because you need the volume. Over time, the cash flow gap widens, and the only solution seems to be asking the bank for a higher limit—which comes with more scrutiny, higher rates, and still doesn’t fix the underlying design flaw.

This connects directly to broader concepts of working capital strain from payment terms and the cash conversion cycle often described in general finance literature. The exercise in this playbook makes those concepts concrete in your kraft-paper-heavy reality.

Map Today’s Reality: How Cash Actually Moves Between You, Suppliers, and Customers

You can’t redesign what you haven’t mapped. The first step is documenting how cash actually moves through your business today.

Create a simple table with your top suppliers and customers. For each supplier, note the payment terms you’re currently operating under, the typical monthly spend, and the actual payment timing—which often differs from contractual terms when you’re stretched. For each customer, note their payment terms, typical monthly sales, and actual payment patterns.

A practical working table might look like this:

| Party | On-paper terms (days) | Actual average (days) | Notes |

| Supplier A (mill) | 30 | 32-35 | Priority supplier, strong history |

| Supplier B (trader) | 45 | 45-50 | Flexible but higher price |

| Supplier C (local) | Advance + 15 | Advance + 20 | Small lots, urgent deliveries |

| Customer X (FMCG) | 60 | 75-80 | Big brand, slow approvals |

| Customer Y (SME) | 45 | 50-55 | Pays after reminders |

| Customer Z (export) | 30 + LC | 30 | Bank processes LC fairly on time |

Then add one more line: average inventory days for kraft paper and finished goods. Consider a hypothetical scenario where reels stay in the warehouse for 12 days on average, and finished boxes stay for another 8 days. This results in roughly 20 inventory days. While your actual numbers will vary significantly based on whether you operate Make-to-Order or Make-to-Stock, the key is consistency in how you measure them. Exact numbers will vary by plant and customer mix; the key is consistency in how you measure them.

This exercise reveals three critical patterns. First, you’ll see where the biggest gaps are. If your largest customer pays in 80 days but your main kraft supplier demands payment in 35 days, that 45-day gap on your largest relationships creates the most strain. Second, you’ll identify outliers—the supplier who quietly accepts 50 days even though the contract says 45, or the customer who consistently pays early. These are data points for negotiation. Third, you’ll spot cumulative effects. Even if individual gaps are small, five suppliers at 35 days and five customers at 75 days create a structural 40-day hole that compounds across all transactions.

Once you have this snapshot, calculate your effective cash conversion cycle. Take your average DSO (how long customers take to pay you) and subtract your average DPO (how long you take to pay suppliers). Add inventory days if you want the full picture. Even a basic formula—total receivables divided by average daily sales—gives a directional sense of collection speed. The result is how many days of cash are locked in operations.

This number is your baseline. Every day you reduce this cycle frees up cash. Conversely, every day it grows puts more pressure on working capital.

The Building Blocks of Payment Terms Design (Supplier Side)

Redesigning supplier payment terms isn’t about demanding longer credit. It’s about creating structures that give you flexibility while addressing supplier concerns about payment security.

Standard credit extension: The most straightforward approach is negotiating longer base terms—moving from 30 to 45 days, or 45 to 60 days. This works when you have leverage through volume, consistency, or competitive alternatives. For kraft paper suppliers, this leverage is often limited, but it’s worth testing with secondary suppliers or during renewal conversations.

Grace days: Some converters use informal grace days—for example, paying on the following Monday if the due date falls on a weekend. These should be treated as part of the real pattern and, where possible, explicitly discussed with suppliers rather than assumed. Making these arrangements visible prevents misunderstandings about late payment.

Early payment discounts: Some suppliers offer 2% to 3% discounts for payment within 10 or 15 days instead of the standard 45 or 60 days. The math here is crucial. A 2% discount for paying 30 days early is equivalent to roughly 24% annual interest—expensive compared to most overdraft rates. These discounts only make sense when you have excess cash, not when you’re managing a tight working capital limit.

Partial advances or deposits: For large or custom kraft paper orders, suppliers might request a 20% to 30% advance payment, with the balance due on standard terms. This protects them against order cancellations while giving you flexibility on the larger portion. The advance is typically due when the order is confirmed, not when goods are delivered, so factor that into cash planning.

Phased credit for volume: If you’re consolidating spend with fewer suppliers, you can sometimes negotiate tiered terms based on volume thresholds. For example, standard 45-day terms up to a certain monthly spend, and 60-day terms above that threshold. This rewards the supplier for the larger, more stable relationship while giving you breathing room on incremental volume.

Split payment structures: For particularly tight cash periods, and assuming market supply isn’t critically constrained, relationship-driven suppliers may consider a split payment schedule—perhaps 50% at 30 days and 50% at 60 days instead of 100% at 45 days. This doesn’t reduce the total cash outflow, but it smooths the timing and can prevent a single large payment from breaching your bank limit.

The key principle is matching the payment structure to your cash flow pattern. If you have predictable monthly cycles, standard terms work fine. If you have lumpy sales or seasonal peaks, phased or split structures reduce the risk of a cash crunch during high-inventory periods.

When evaluating supplier payment terms, always convert them to a “cost of capital” equivalent. If a supplier offers 60-day terms at a 3% price premium versus 30-day terms at list price, you’re effectively paying 36% annual interest for that extra 30 days of credit. Compare that to your bank overdraft rate—which typically ranges from Prime plus a margin (often 8% to 15% depending on your region and credit rating)—and the bank facility is usually the cheaper option.

The Building Blocks of Payment Terms Design (Customer Side)

Customer payment terms are harder to control, but there are still design opportunities that reduce cash flow strain without losing the relationship.

Credit days and the “stretch” factor: Start by calculating a simple DSO for your key customers over the past 12 months. Then compare on-paper terms (say, 60 days) with actual average timing (perhaps 74 days). The difference between the two is the stretch. This stretch is usually driven by document issues, internal approval cycles at the customer, monthly payment runs, or a simple habit of paying “when reminded.” When designing payment terms, treat actual timing as the baseline, not the contract.

Shorter base terms for new customers: When onboarding new customers, you have more leverage to set favorable terms. Instead of defaulting to their requested 75 or 90 days, propose 45 or 60 days with a review after six months once payment history is established. Many customers accept this because it’s reasonable and temporary.

Early payment incentives: Offering a 1% to 2% discount for payment within 15 or 30 days can accelerate cash inflow. The math needs to work—a 2% discount for a 30-day acceleration is expensive—but for customers who have cash and appreciate the savings, it’s a win-win. This works particularly well with smaller customers who don’t have rigid payment cycles.

Deposit or milestone payments for large orders: For significant custom orders, request a 20% to 30% deposit upfront, with the balance due on delivery or net-30 from delivery. This reduces your exposure and provides cash to fund the kraft paper purchase. The deposit shifts part of the working capital burden back to the customer.

Progress billing for long-lead projects: If you’re producing a large order over several weeks, break the invoice into milestone payments—30% on order confirmation, 40% on production completion, and 30% on delivery. This prevents waiting 90 days for the entire payment and aligns cash in with cash out as you pay suppliers incrementally.

Retention for payment reliability: For customers with poor payment history, consider asking for a small retention—perhaps 5% to 10% of each invoice held until the next invoice is paid on time. This creates an incentive for timely payment without requiring confrontational collection calls.

The challenge on the customer side is that most converters feel they lack leverage. Large customers dictate terms, and pushing back risks losing the business. This is where the next step—scenario design—becomes critical. You’re not trying to win every negotiation, but rather to strategically improve terms where you have the most impact and the best chance of success.

Designing Scenarios to Align Cash In and Cash Out

With building blocks understood, the next step is designing payment term scenarios that reduce your cash conversion cycle without requiring universal changes. Focus on high-impact, low-risk moves.

Instead of chasing one perfect set of terms, design a few realistic combinations and test how they affect your cash gap. A simple way to start is to sketch three scenarios:

- Baseline scenario – today’s actual behavior

- Stability-first scenario – modest shifts that smooth out the worst gaps

- Stretch scenario – more ambitious rebalancing where you have leverage and strong relationships

A concrete example: 15 days that change your cash gap

Consider one high-volume supplier and one major customer operating under today’s terms:

- You pay the supplier in 35 days

- You hold average inventory for 20 days

- You collect from the customer in 75 days

The cash cycle for this stream looks like:

- Day 0: Kraft paper arrives

- Day 35: Cash goes out to the supplier

- Day 55: Boxes are sold and delivered (after 20 days of inventory and processing)

- Day 75: Cash comes in from the customer

Your cash out precedes cash in by about 40 days (from Day 35 to Day 75). That’s 40 days of cash tied up in this single relationship.

Now imagine a stability-first scenario where the supplier moves from 35 to 45 days, and the customer—through a mix of better documentation and modest term adjustment—moves from 75 to 60 days. The picture becomes:

- Day 0: Paper arrives

- Day 45: Cash goes out

- Day 55: Boxes delivered

- Day 60: Cash comes in

Your cash gap for this stream shrinks from roughly 40 days to 15 days. Exact numbers will differ by plant and product mix, but the principle holds: small adjustments on both sides often create outsized relief.

Additional scenario patterns:

Match longest customer terms to longest supplier terms: Identify your customer with the longest payment terms—say, 90 days. Then identify your supplier with the most flexible payment terms or lowest volume. Negotiate to extend that supplier’s terms to match your longest customer, creating a balanced “90 in, 90 out” pair.

Tiered customer terms based on payment reliability: Segment customers into three groups: always pay on time, usually pay on time, and frequently pay late. Offer the “always on time” group extended terms as a reward. For the “frequently late” group, shorten terms to 45 days or require deposits. This shifts your cash flow toward more predictable customers.

Offset early payment discounts with supplier negotiations: If three of your suppliers offer early payment discounts, calculate the total annual cost of taking those discounts. Use that number in negotiations with your main kraft paper supplier: “We’re spending $X annually on early payment discounts with other suppliers. If you can extend our terms from 45 to 60 days with no discount, we’ll consolidate that volume with you instead.”

Test scenarios against your working capital limit: Once scenarios are sketched, estimate the peak cash out in each scenario—how much money is out at risk (inventory plus receivables minus payables) before customer cash arrives. Compare this to your existing bank limit and how close you typically are to breaching it in busy months. Even simple approximations on a spreadsheet can show which scenario is safer versus too aggressive.

Negotiating Payment Terms Without Burning Bridges

Payment terms are relationship-sensitive. Pushing too hard damages trust; asking too timidly yields no improvement. The approach depends on your leverage and the relationship’s importance.

For critical kraft paper suppliers where you have low leverage:

Don’t open by demanding better terms. Instead, ask for their input: “We’re reviewing our payment terms across all suppliers to improve cash flow predictability. What flexibility exists in your standard terms, and what would you need from us to consider an extension?” This frames the conversation as collaborative, not adversarial. Suppliers often reveal options you didn’t know existed—like split payments or volume-based terms.

If they say no to term extensions, ask about structural alternatives: “Would you consider a deposit on large orders instead of extending terms on all orders?” or “If we committed to a minimum monthly volume, would that open up better terms?” The goal is finding a trade that addresses their concern (payment security) while giving you relief (better cash timing).

For customers where you have moderate leverage through quality or reliability:

Frame better payment terms as mutually beneficial. For new customers, it’s simple: “Our standard terms for new relationships are 45 days while we establish payment history, with a review at six months.” For existing customers, tie term changes to value: “We’re offering early payment discounts to customers who can accelerate payment. If you can move from 75 to 60 days, we’ll offer a 1% discount.”

Avoid framing payment terms as a problem they created. Instead, position it as an improvement you’re rolling out: “We’re streamlining our payment terms to be more consistent across customers. Starting next quarter, we’re moving to 60-day terms for all established customers, down from the 75 to 90 days we’ve been operating under. This helps us maintain competitive pricing and service quality.”

A practical script for customer discussions:

“Over the last 12 months, our actual collection days with you have averaged around 78, even though we’re invoicing on 60-day terms. To keep supply stable without over-stretching our bank limits, could we jointly explore a slightly different structure—either bringing collections closer to the agreed 60 days, or splitting payments for larger orders? We can test this for a few months and review.”

For any negotiation:

Always present the request in writing with clear effective dates and examples. Ambiguity creates disputes. If you agree to phased payments, document exactly when each payment is due relative to specific milestones. If you negotiate deposit terms, specify the percentage, the triggering order size, and the payment due date.

Give advance notice—at least 30 days before new terms take effect. Springing changes on suppliers or customers damages the relationship more than the terms themselves. The notice period shows respect and gives them time to adjust their own cash flow planning.

Finally, be prepared to walk away from the worst relationships. If a customer demands 120-day terms and you’re constantly chasing payment, the margin erosion and cash flow strain aren’t worth keeping the business. Use alternative supplier networks to reduce dependence on any single kraft paper supplier who refuses reasonable terms.

Turning Your New Payment Terms Design into a Living System

Payment terms aren’t a one-time fix. Customer mix changes, supplier relationships evolve, and your cash position improves or deteriorates. Treating payment terms as a living system prevents future drift.

Centralize the information: Maintain a single, controlled sheet (or simple internal dashboard) listing key suppliers and customers, on-paper terms and observed behavior, and any temporary arrangements or pilots.

Set a quarterly review cycle: Every 90 days, update your supplier and customer payment terms map. Flag any changes—new suppliers added, customers who shifted payment behavior, terms that were informally extended during tight periods and never formalized. This review takes 30 minutes but prevents the slow accumulation of problematic terms.

Track actual payment timing separately from contractual terms: A customer with “net 60” terms who consistently pays in 75 days has an effective 75-day term in your cash flow planning. Don’t anchor to the contract; anchor to reality. When actual timing drifts beyond contractual terms, address it immediately with a polite payment reminder that references the agreed terms.

Classify relationships by health: A pragmatic view might classify relationships into three categories:

- Healthy, aligned: Cash in and cash out timings broadly match; DSO and DPO are stable

- Manageable but watch: Minor stretches or occasional spikes that could become problematic if volumes grow

- High-risk, misaligned: Large and persistent gaps, heavy reliance on overdraft, or repeated tensions

This classification helps you prioritize which relationships need attention first and which can continue as-is.

Build payment terms into your quoting process: Before finalizing pricing for a new customer, confirm their requested payment terms and adjust your margin accordingly. A customer demanding 90-day terms should carry a higher price than a customer accepting 45-day terms, because you’re effectively financing their purchase for an extra 45 days.

Create a simple dashboard with three metrics: Average DSO, average DPO, and cash conversion cycle. Update these monthly. If DSO creeps up from 70 to 80 days over three months, that’s a signal to tighten collection efforts or revisit customer terms. If DPO drops because you’ve been paying suppliers early to preserve relationships, you’ll see the impact on working capital immediately.

Ensure cross-functional visibility: Owners, finance teams, procurement, and sales should share the same picture. Sales should not promise terms that finance cannot support; procurement should not agree to advances that sales cannot offset.

By treating payment terms design for kraft paper suppliers and customers as an ongoing process rather than a one-time event, converters can steadily move more relationships into the “healthy, aligned” zone.

Where PaperIndex Fits (and Where It Doesn’t)

Payment terms design is ultimately about choices and leverage. More supplier options give you the ability to shift volume when terms become unsustainable. More customer options reduce dependency on any single buyer who demands unfavorable terms.

PaperIndex functions as a discovery platform that expands those options. If your current kraft paper supplier refuses to extend terms from 45 to 60 days, exploring alternative suppliers gives you data points for negotiation or outright alternatives. Knowing you can source the same grade kraft paper from three suppliers at competitive pricing strengthens your position in payment term discussions.

On the customer side, diversifying your buyer base through platforms like PaperIndex reduces the leverage any single customer has over your payment terms. If 60% of your revenue comes from one customer demanding 90-day terms, you have no negotiating power. If that concentration drops to 30% because you’ve added new buyers through RFQ submissions, you can afford to push back or even walk away if terms become untenable.

However, PaperIndex doesn’t provide financing, doesn’t extend credit, and doesn’t manage payment terms on your behalf. It’s a connector between buyers and suppliers—all payment terms and negotiations happen directly between you and your trading partners. Think of it as expanding the pool of options, not as a solution to cash flow problems.

For converters who are not yet listed, a natural step after doing the mapping and scenario work in this article is to join PaperIndex free to widen future options. By discovering more supplier profiles and exploring relevant kraft paper buyer listings over time, converters can build backup sources and reduce dependence on a small number of relationships. Tools such as contact suppliers and contact buyers support this ongoing discovery process.

Next Best Steps: What to Do This Week

Payment terms redesign can feel overwhelming, but you can make meaningful progress this week with three focused actions.

Action 1: Map your current reality

Create the table described earlier. List your top five kraft paper suppliers with their current payment terms, monthly spend, and actual payment timing. Do the same for your top five customers with their payment terms, monthly revenue, and actual payment timing. Add your inventory days. This takes 45 minutes and immediately shows where the biggest cash flow gaps exist.

Action 2: Calculate your baseline cash conversion cycle

Take your average DSO (total receivables divided by daily sales) and subtract your average DPO (total payables divided by daily purchases). The result is your baseline in days. If you want a more complete picture, add inventory days (inventory value divided by daily cost of goods sold). This number becomes your improvement target.

Action 3: Design 2-3 realistic scenarios

Create a baseline, a stability-first scenario, and a stretch scenario. Focus on the top few relationships that drive most of your tonnage and receivables. Pick one supplier and one customer as pilots—choose relationships where trust already exists. Test modest changes first, such as tightening actual payment behavior to match agreed terms or small shifts in days.

Action 4: Review impact on your working capital limit

After a few billing cycles, look at whether overdraft usage is smoother and whether supplier calls and bank pressure have reduced. Adjust scenarios as needed based on real results.

Don’t try to redesign everything at once. One successful scenario builds confidence and provides a template for future negotiations. Over the next quarter, you can tackle a second scenario, then a third. Within a year, you’ll have fundamentally reshaped your payment terms architecture without burning relationships or creating operational chaos.

The goal isn’t perfection—it’s progress. Every five-day reduction in your cash conversion cycle frees up working capital. Every supplier relationship where you move from 30 to 45-day terms reduces the pressure on your bank limit. Small wins compound, and over time, the cumulative effect is a cash flow system you control instead of one that controls you.

Disclaimer: This article provides general educational information about payment terms design concepts. It does not constitute financial, legal, or professional advice. Payment term structures and contract negotiations involve legal and financial considerations specific to your business and jurisdiction. Consult qualified legal and financial professionals before implementing changes to supplier or customer payment terms.

Our Editorial Process

Our expert team uses AI tools to help organize and structure our initial drafts. Every piece is then extensively rewritten, fact-checked, and enriched with first-hand insights and experiences by expert humans on our Insights Team to ensure accuracy and clarity.

About the PaperIndex Insights Team

The PaperIndex Insights Team is our dedicated engine for synthesizing complex topics into clear, helpful guides. While our content is thoroughly reviewed for clarity and accuracy, it is for informational purposes and should not replace professional advice.