📌 Key Takeaways

A compliance certificate proves testing happened—not that the testing covers your actual use case.

- Certificates Expire Faster Than Paper: Compliance documents reflect past test conditions, so supplier changes to ingredients, factories, or processes can silently break your coverage.

- Request an Evidence Bundle, Not a Logo: A single certificate leaves gaps; ask for compliance statements, test reports, lot numbers, and shipment links all connected together.

- Match Tests to Your Real Conditions: A supplier tested for cold foods at 40°C cannot claim compliance for your hot-fill line at 85°C without new proof.

- Trace Every Lot Back to Its Proof: If you cannot connect the test data in your file to the specific shipment in your warehouse, you have no defensible record.

- “Needs Clarification” Is a Valid Decision: When evidence is incomplete, pausing for answers beats forcing a risky yes or no that fails during inspection.

Verified suppliers protect your supply chain—hopeful assumptions do not.

Procurement managers and compliance professionals auditing food-contact packaging suppliers will gain a repeatable verification method here, preparing them for the detailed workflow that follows.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The certificate satisfies nothing.

A PDF lands in your inbox—ISEGA logo, FDA compliance claim, official-looking test dates. Your procurement checklist shows a green box. The supplier is “approved.” But six months later, a routine inspection surfaces a gap: the test conditions don’t match your actual use case.

The certificate was real. The protection was not.

This is the compliance trap that catches experienced buyers. You verify that documents exist without verifying what those documents actually prove. The result is a supplier file that looks complete but cannot withstand scrutiny from regulators, auditors, or your own QA team when something goes wrong downstream.

The Compliance Shield is a repeatable audit method that turns supplier paperwork into a defensible Pass, Fail, or Needs Clarification decision by demanding an evidence stack, validating scope, and enforcing lot-level traceability—reconciling documentation against specific production batches—before approval. This audit protocol defines the specific requirements for validation, evidence collection, and lot-level reconciliation necessary for pre-shipment approval.

What “FDA & ISEGA Safety” Means in Supplier Audits (and What It Does Not)

“FDA & ISEGA safety” in an audit means evidence-backed suitability for intended food-contact use—not a logo-based guarantee of universal compliance.

A food-contact safety audit verifies that a supplier can demonstrate—through traceable documentation—that their food packaging paper meets the requirements for your intended use conditions. It does not verify that the supplier’s products are inherently “safe” in all contexts, nor does it replace product-specific suitability testing.

Three distinct concepts often get conflated during procurement discussions, and separating them is essential for effective supplier evaluation.

Safety audit refers to the systematic review of a supplier’s compliance documentation, testing evidence, and traceability systems. It answers one question: can this supplier prove that their materials are appropriate for the food-contact conditions you specify? The audit is your verification process—not a guarantee, but a structured method for gathering and evaluating evidence.

Certification is a subset of this larger picture. A certificate—whether referencing FDA regulations or ISEGA recommendations—is a declaration that certain tests were performed under certain conditions. It represents evidence, not proof of suitability for your specific application. A certificate that tests migration at 40°C for 10 days tells you nothing about performance at 85°C during hot-fill operations.

Product suitability stands apart from both concepts. Even a fully compliant, well-documented supplier may produce materials unsuitable for your specific application. Suitability requires matching the supplier’s tested conditions to your actual use case—the food types you package, the temperatures involved, the duration of contact.

The audit workflow that follows treats supplier documentation as claims requiring verification rather than credentials warranting automatic acceptance. This shift—from trust to verification—prevents the certificate-only blind spots that surface during inspections.

Common Audit Traps to Avoid

“FDA certified”: FDA generally does not operate as a consumer-style certification logo for packaging materials. Treat “FDA approved” or “FDA certified packaging” claims as a prompt to request the underlying regulatory basis and scope, not as proof.

“ISEGA certificate = safe for everything”: Certificates are scoped. A certificate may apply to a specific product grade, composition range, and use conditions; it should not be treated as blanket coverage for all variants, coatings, or converters.

“Compliance = one document”: Real confidence comes from aligned documents—a complete packet that matches the legal entity, product code, composition, intended use, and the lot being shipped.

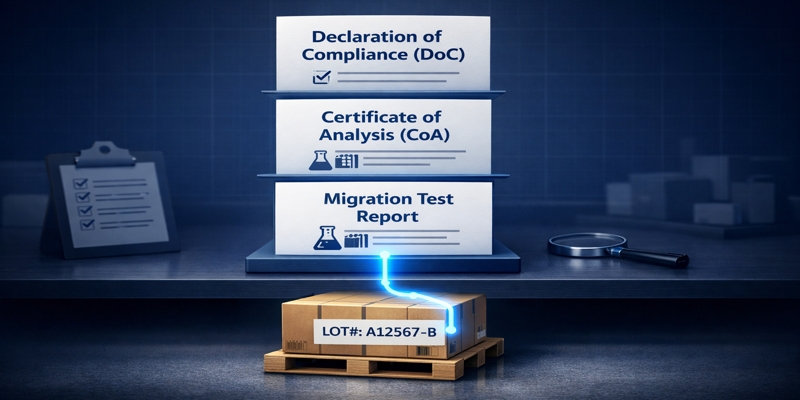

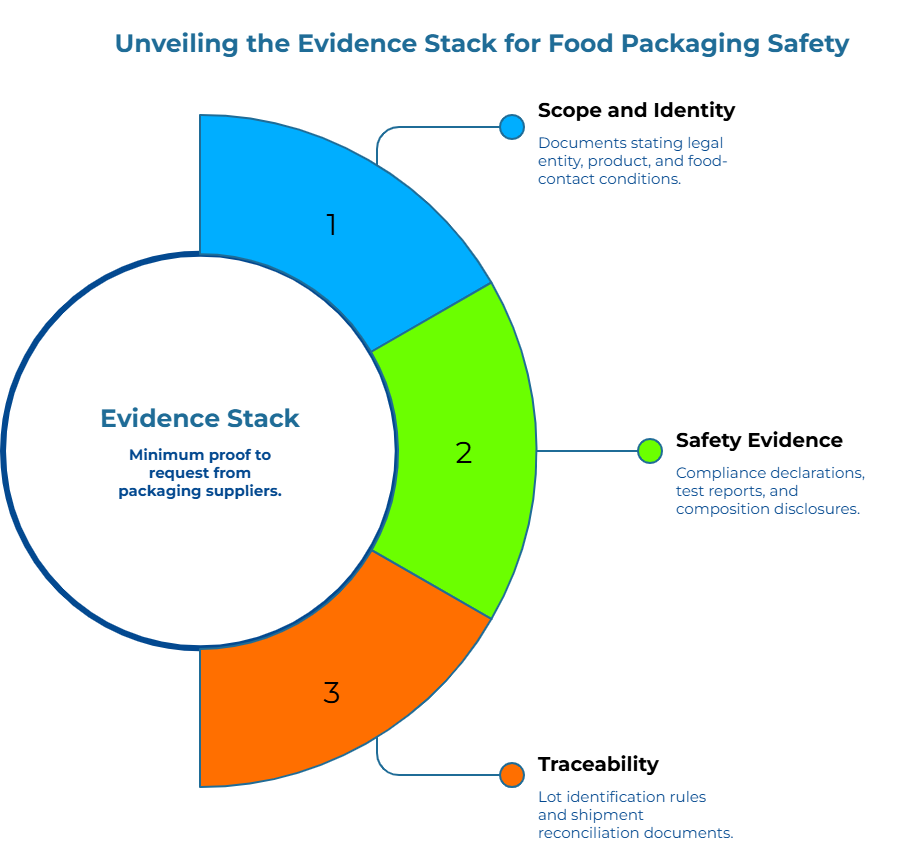

The “Evidence Stack”: The Minimum Proof to Request from a Packaging Supplier

A defensible supplier audit starts by requesting a minimum evidence stack that proves scope, safety basis, and traceability before any commercial approval. Requesting only a certificate leaves gaps that inspectors will find.

Think of the stack in three layers: scope and identity, safety evidence, and shipment-level traceability.

Layer 1: Scope and Identity

Request documents that clearly state the legal entity name and manufacturing sites, product name or grade with revision and internal codes, composition boundaries including coatings, inks, and adhesives where applicable, and intended food-contact conditions covering dry, moist, or fatty foods along with temperature, time, and whether contact is direct or indirect.

Layer 2: Safety Evidence

Depending on jurisdiction and material, this layer includes several document types.

Declaration of Compliance (DoC) forms the foundation. This formal statement from the supplier—or their raw material supplier—confirms that materials comply with stated regulations for specified use conditions. A properly constructed DoC names the regulatory framework (FDA 21 CFR 176.170, EU 1935/2004, or similar) and specifies the intended food types and contact conditions. Vague declarations claiming compliance “for all food contact applications” without specifying conditions represent a red flag, not reassurance.

For U.S. markets, FDA describes the use of a Letter of Guaranty under 21 CFR 7.12/7.13 as a form of assurance for food-contact use. This formal mechanism provides suppliers a structured way to communicate compliance status for intended applications.

Certificate of Analysis (CoA) provides lot-specific test results showing actual measured values against specification limits. The CoA should reference the test method used, the laboratory that performed the testing, the date of analysis, and—critically—the specific lot or batch number. Generic CoAs referencing “typical production” rather than specific lots cannot establish traceability to your actual inventory.

Migration test reports demonstrate that substances do not transfer from packaging to food above permitted limits. These reports should specify the simulant used (representing fatty, aqueous, acidic, or dry foods), the time and temperature conditions of the test, and the specific migration limits tested. Both overall migration limits and specific migration limits for named substances may be relevant depending on your application and regulatory jurisdiction.

Composition disclosure addresses the materials themselves. For paper-based food packaging sourced from food packaging paper suppliers, this typically includes confirmation of fiber sources, coatings, inks, and adhesives—each of which may require separate compliance verification. A paper substrate from food grade kraft paper suppliers that meets food-contact requirements can become non-compliant when combined with an unverified coating or printing ink.

Layer 3: Traceability (Document to Lot to Shipment)

This layer is where audits often fail. Require lot or batch identification rules explaining how lots are defined, where codes are printed, and how they map to documentation. Request Certificates of Analysis or lot records tied to shipped lots where applicable. Gather shipment documents that allow reconciliation—purchase orders, packing lists, bills of lading, and pallet labels—with lot IDs captured in at least one controllable place.

Traceability documentation provides the essential link between a specific shipment you receive and the test reports that apply to it. Without lot-level traceability, you cannot prove that the test evidence in your file actually covers the inventory sitting in your warehouse.

A complete evidence stack connects every claim to a test report, every test report to a lot number, and every lot number to a shipment.

“Complete Packet” vs. “Partial Packet” vs. “Fragmented Packet”

| Packet Quality | What It Looks Like | Audit Risk |

| Complete | Clear scope, safety basis, test evidence, and lot/shipment linkage all aligned | Lowers professional risk; supports defensible approval |

| Partial | Certificate or logo with vague “food grade” statement; no conditions of use; no lot mapping | High risk of approval on non-verifiable claims |

| Fragmented | Good evidence exists but names, versions, or product codes are mismatched across documents | Medium-to-high risk until reconciled |

The difference between these categories often determines whether your compliance file survives inspection.

For detailed guidance on evaluating documentation fields across different certificate types, see this field-by-field documentation checklist.

FDA vs. ISEGA: What Changes in Procurement Questions

FDA and ISEGA represent different regulatory frameworks with different verification requirements. Understanding what each framework signals—and what it does not—changes the questions you ask during procurement.

| Aspect | FDA (U.S.) | ISEGA (Europe/International) |

| What it is | U.S. regulatory system governing food-contact substances and indirect additives | Independent lab and certification body providing testing and conformity evaluation services |

| Who issues | Self-declaration by manufacturer based on FDA regulations (21 CFR) | Third-party certification body (ISEGA institute) |

| What buyers typically see | Assurance letters, regulatory basis references, food-contact substance status evidence | Certificate or attestation with test scope, often product- and use-specific |

| What it signals | Materials comply with FDA’s list of permitted substances for food contact under stated conditions | Materials were tested against European food contact standards (typically EU 1935/2004, EU 10/2011 for plastics) for a defined scope |

| Common misread | Assuming FDA “approval” exists (FDA does not approve food-contact materials; it permits substances) | Assuming ISEGA certification covers all use conditions (it covers tested conditions only) |

| Key procurement question | “Which intended conditions of use are covered, and what is the regulatory basis?” | “What exact grade, composition, and conditions are covered, and how does it map to today’s shipment?” |

The critical difference lies in the verification structure. FDA compliance is typically self-declared by the manufacturer, meaning you rely on the supplier’s interpretation of regulations and their internal testing protocols. ISEGA involves third-party testing, but only for the conditions specified in the test protocol—not for every possible application.

Neither framework guarantees suitability for your application. Both require you to match documented test conditions against your actual intended use. A supplier with ISEGA certification for cold-fill applications cannot claim compliance for your hot-fill line without additional evidence covering those specific conditions.

When evaluating suppliers operating under either framework, the fundamental question remains the same: does the empirical data align with the intended environment? The framework tells you who made the compliance determination; your audit tells you whether that determination applies to your situation.

Authoritative references for validating claims:

- FDA Inventory of Effective Food Contact Substance (FCS) Notifications

- FDA Letter of Guaranty for products intended for food-contact use

- ISEGA food-contact materials testing and services

For broader context on verifying different certification types, see this verification guide for certifications.

Key Criteria for Decision Making: Gates and Quality Signals

A supplier passes this audit only when scope is explicit, evidence is coherent, and traceability to the shipped lot is demonstrated.

Separate your evaluation criteria into two categories: gates are must-have requirements that determine pass or fail, while quality signals are risk-reduction factors that strengthen confidence in an approval decision.

Gate 1: Scope Fit (Mandatory Requirement)

Intended food type and contact mode are stated, covering direct versus indirect contact and whether foods are dry, moist, or fatty. Temperature and time expectations are stated or bound. Covered components are explicit, including base paper plus coatings, inks, and adhesives where relevant.

Gate 2: Identity Integrity (Mandatory Requirement)

Legal entity matches across documents with no unexplained parent or subsidiary mismatch. Product code or grade matches across all documents. Document versions are current and not contradictory.

Gate 3: Evidence Coherence (Mandatory Requirement)

Safety assurance references an identifiable basis and conditions. Test reports, if provided, match the material system and stated use conditions. Restrictions and exclusions are disclosed rather than buried.

Gate 4: Traceability (Mandatory Requirement)

Lot or batch identification exists and is usable. A document can connect the shipped lot to the audited evidence, maintaining the chain from document to lot to shipment.

Quality Signals (Risk-Reduction)

A clear change-control process defines what triggers re-approval. Document renewal cadence exists, such as annual review or review upon formulation changes. Fast, precise responses to clarification questions serve as a strong proxy for process maturity—a trait that distinguishes reliable paper suppliers from those managing compliance reactively.

The Compliance Shield Audit Workflow (Step-by-Step)

This workflow transforms supplier evaluation from document collection into evidence verification. Each step builds toward a defensible Pass, Fail, or Needs Clarification decision. The sequence follows a logical progression: request, validate, reconcile, decide, file.

Step 1: Baseline Requirement Definition. Before contacting suppliers, document your specific requirements. What food types will contact the packaging—aqueous, fatty, acidic, dry? What temperatures will occur during filling, storage, or heating? How long will food remain in contact with the packaging? Which regulatory jurisdictions must you satisfy? This documentation becomes your audit baseline—the standard against which you evaluate all supplier evidence.

Step 2: Evidence Stack Acquisition. Ask for all document categories in a single email with a clear checklist: DoC, CoA, migration test reports, composition disclosure, and traceability documentation. Specify explicitly that you need lot-level traceability, not generic “product line” documentation. Suppliers accustomed to providing only certificates may need clear guidance on what constitutes a complete evidence packet.

Step 3: Verify document authenticity. Check that supplier names, addresses, and registration numbers match across all documents. Confirm that test laboratory names are real and, where possible, accredited for the relevant test methods. Look for consistent date formatting and document reference numbers. Discrepancies between the company name on a certificate and the entity on your purchase order warrant clarification before proceeding.

Step 4: Check scope statement first (before reading test details). Compare the documented scope against your use conditions from Step 1. If conditions of use are missing, stop and classify as Needs Clarification. Do not proceed to evaluate test data until you have confirmed scope alignment.

Step 5: Review the safety basis. Look for regulatory basis references (specific 21 CFR sections, EU regulations) and explicit restrictions. Confirm the claim is about the shipped article, not a generic material family. For U.S. regulatory context, FDA maintains pages on food-contact substances and effective notifications that help validate supplier claims.

Step 6: Validate test evidence (if provided). Ensure the tested sample, method family, and conditions are aligned to intended use. If conditions differ materially, classify as Needs Clarification or Fail if the mismatch is fundamental. A test using aqueous simulant at 40°C does not demonstrate suitability for fatty foods at 70°C.

Step 7: Enforce traceability: document to lot to shipment. Ask where the lot code appears—pallet label, CoA, packing list. Require at least one reliable mapping artifact. Verify that the CoA and test reports reference specific lot or batch numbers—and that those numbers appear on shipping documentation for materials you actually receive. If the supplier can only provide “representative” test data that doesn’t link to specific production lots, this represents a traceability gap requiring resolution.

Step 8: Reconcile discrepancies and issue clarification requests. Document any mismatches you identified: names that don’t align across documents, test conditions that don’t cover your use case, missing lot numbers, unclear test methods. Send specific, written questions to the supplier. Avoid vague asks like “please confirm compliance.” Instead, ask precisely: “Please provide migration test data for fatty food simulant at 70°C for 2 hours, matching our hot-fill application.” Specific questions yield specific answers; vague questions yield reassurances.

Step 9: Evaluate supplier response quality. A compliant supplier responds with specific documents, not verbal reassurances. Responses should directly address your questions with referenced evidence. If responses are delayed beyond reasonable timeframes, vague in their substance, or redirect you to generic certificates you’ve already reviewed, this represents decision-relevant information—not merely an inconvenience.

Step 10: Verification Outcome Assignment. Based on the evidence gathered, assign one of three outcomes using the decision tree in the following section. Attach a short rationale referencing the gates you evaluated.

Step 11: Archival and Renewal Protocols. Store all documents, correspondence, and your decision rationale in a single supplier file. Include the date, the reviewer’s name, and the decision outcome. Set renewal triggers for both date-based review and change-based review. This file becomes your evidence trail—the documentation that demonstrates your verification process during inspections or internal reviews.

Handling Supplier Resistance

Some suppliers may insist that “the certificate covers everything” or decline to provide lot-specific data. This response itself constitutes decision-relevant information.

Reframe the request as risk management: “The organization needs a defensible record that links scope and evidence to the lot being supplied.” Narrow the ask: “Which exact grade and which exact intended conditions of use are covered?”

If the supplier cannot produce a lot-level mapping method, treat it as a systemic control gap. A supplier with robust compliance systems can produce evidence; resistance to reasonable documentation requests suggests either capability gaps or organizational unwillingness to support buyer verification. Either warrants caution.

For additional guidance on audit decision criteria, see this factory audit decision checklist.

Red-Flag Checklist: Fast Ways to Spot Weak Documentation

Red flags are patterns that predict audit failure because they break identity, scope, evidence coherence, or traceability. Systematic audits take time. This checklist helps you identify high-risk documentation quickly, before investing in full verification.

Document Integrity Flags

Mismatched entity names across documents—where the supplier name on a certificate differs from the company issuing invoices or shipping documents—suggest either administrative carelessness or deliberate misrepresentation. Either undermines confidence in the documentation chain.

Missing or inconsistent dates raise questions about document validity. Test reports without dates cannot be verified for currency. Dates predating the supplier’s stated production start suggest recycled documentation from previous operations or different facilities.

Generic scope language, such as DoCs claiming compliance “for all food contact applications” without specifying conditions, indicates either lack of understanding about compliance requirements or intentional vagueness. Neither supports buyer confidence.

Untraceable laboratory references—test reports citing laboratories you cannot verify through accreditation databases or basic internet searches—may indicate fabricated documentation or reliance on unqualified testing facilities.

Testing Clarity Flags

Vague test methods referencing “internal methods” rather than recognized standards (FDA methods, EN standards, ISO protocols) prevent meaningful evaluation of test validity. Standardized methods exist precisely to enable comparability and verification.

Missing test conditions represent a fundamental gap. Migration data without specification of simulant type, temperature, or duration cannot be matched to your use case. The numbers are meaningless without the context of how they were generated.

Overbroad claims stating that materials “pass all migration limits” without listing which specific substances were tested suggest either testing gaps or deliberate vagueness. Comprehensive compliance requires testing relevant to the specific materials and their potential migrants.

Old test data—reports dated more than two to three years ago without confirmation that formulation has not changed—may no longer reflect current production. Material suppliers change. Formulations evolve. Testing conducted on different materials provides no assurance about current products.

Test reports that do not identify the tested article clearly enough to match production grade cannot be linked to your actual supply.

Traceability Gap Flags

Absence of lot numbers on CoAs or test reports—documents referencing “product type” rather than specific production batches—prevents any connection between test evidence and your actual inventory. Generic testing may demonstrate capability; it cannot demonstrate that specific materials you receive were tested.

Broken chains occur when lot numbers on shipping documents do not appear on any test documentation in your file. The shipment and the evidence exist independently, with no verified connection between them.

Single-source dependency, where all compliance documents originate from the supplier with no third-party verification of any kind, concentrates risk. Self-declaration has its place, but some independent verification—whether laboratory testing or certification body involvement—provides additional assurance.

Process Control Flags

Absence of change notification commitment—where the supplier has no stated policy for informing buyers of formulation changes—creates ongoing risk. A material that meets requirements today may be reformulated tomorrow without your knowledge, invalidating your compliance documentation.

Incomplete supply chain visibility, where suppliers cannot identify their raw material sources or confirm upstream compliance, suggests either opacity or lack of control over their own inputs. Paper-based packaging compliance depends on the entire material chain, not just final conversion.

Inconsistent document formats, where each request yields documents in different formats and structures, suggest ad-hoc rather than systematic compliance management. Organized suppliers maintain organized documentation systems.

No defined renewal cadence for compliance documentation—relying on “we’ve always done it this way” rather than evidence when asked about scope—indicates process immaturity.

Any single flag may have a reasonable explanation. Multiple flags appearing in the same supplier file warrant escalation—either to Needs Clarification status requiring resolution or to Fail status if patterns suggest systemic problems rather than isolated issues.

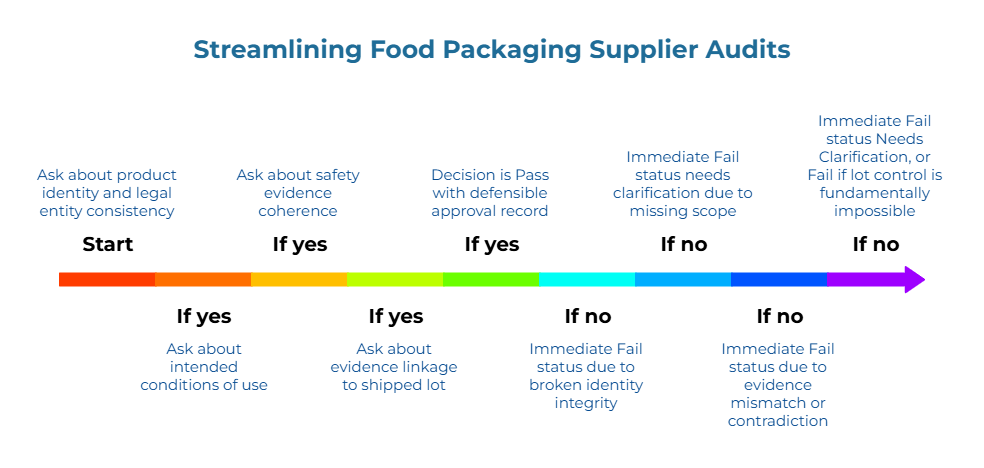

Decision Tree: Pass / Fail / Needs Clarification

A clean decision tree protects both safety and credibility by making “uncertainty” a valid outcome instead of forcing a risky yes or no. The audit workflow produces evidence. The decision tree converts that evidence into action. Lot-level traceability, confirmed through your audit process, enables defensible pass/fail supplier decisions that can withstand internal review and external inspection.

Decision Logic Flow

Start by asking whether product identity and legal entity are consistent across documents. A negative response triggers an immediate Fail status due to broken identity integrity.

If yes, proceed to ask whether intended conditions of use are explicitly covered (scope fit). A negative response triggers an immediate Fail status needs clarification due to missing scope.

If yes, proceed to ask whether safety evidence is coherent for the material system and conditions. A negative response triggers an immediate Fail status due to evidence mismatch or contradiction.

If yes, proceed to ask whether evidence can be linked to the shipped lot, maintaining the chain from document to lot to shipment. A negative response triggers an immediate Fail status Needs Clarification, or Fail if lot control is fundamentally impossible. If yes, the decision is Pass with a defensible approval record.

Status: Approved for Specified Use

All of the following conditions must be satisfied:

The DoC explicitly names your regulatory framework and specifies intended use conditions that encompass your actual application. Migration test conditions match or exceed your actual use case requirements—the tested temperatures, times, and food simulants are at least as demanding as your real-world conditions. Lot-level traceability links specific test data to incoming shipments you receive, creating a documented chain from testing through delivery. No unresolved red flags remain from the checklist evaluation. The supplier responded to all clarification requests with specific documentation rather than general assurances.

A Pass decision means you have verified that this supplier can provide documented evidence of compliance for your specified use conditions. It does not guarantee compliance for different conditions, nor does it eliminate the need for ongoing verification as materials and formulations may change.

Status: Pending (Requires Additional Evidence)

Any of the following conditions triggers this status:

Test conditions partially match your use case but gaps remain requiring additional data or explanation. The supplier provided incomplete responses to specific questions, answering some inquiries while leaving others unaddressed. Documentation exists but lot-level linkage is unclear—you have test reports and you have shipping records, but the connection between them requires clarification. Minor red flags were identified that may have reasonable explanations you have not yet received.

A Needs Clarification decision represents an active status, not a holding pattern. Define specific information required for resolution, communicate those requirements clearly to the supplier, and establish a reasonable timeframe for response. If clarification requests remain unresolved beyond that timeframe, the status should convert to Fail.

Status: Rejected

Any of the following conditions triggers this status:

Test conditions do not cover your use case and the supplier cannot provide additional data addressing the gap. The supplier is unresponsive to reasonable documentation requests or provides only generic reassurances rather than specific evidence. Multiple red flags appear with no credible explanation addressing the pattern. Traceability cannot be established between test data and shipped product despite reasonable effort to clarify. The DoC claims compliance without any supporting test evidence to substantiate the claim.

A Failed decision is not necessarily permanent. Suppliers can address documentation gaps, conduct additional testing, or improve their compliance systems. A supplier that fails initial audit may pass future evaluation after addressing identified deficiencies. The Fail status reflects current evidence, not permanent judgment about the supplier’s capabilities.

Illustrative Examples

Compliant Documentation Flow: A paper-based food wrap supplier—one of many paper manufacturers serving the packaging sector—provides a DoC citing FDA 21 CFR 176.170 for fatty foods at temperatures up to 100°C. The accompanying CoA lists lot numbers matching your purchase order. Migration test reports show testing with fatty food simulant at 100°C for 30 minutes—exceeding your actual use case of 70°C for 15 minutes. The supplier has provided a signed change-notification commitment. No red flags were identified during review. Decision: Pass for the specified application.

Non-Aligned Use-Case Scope: A corrugated box supplier provides an ISEGA certificate with accompanying test reports. Review reveals that migration testing used dry food conditions only. Your application involves indirect contact with moist foods through wrapped products. The supplier has been responsive to inquiries but has not yet provided supplemental test data covering aqueous conditions. Decision: Needs Clarification. Action required: Request migration data using aqueous food simulant before approval can be granted.

Failure to Substantiate Claims: A packaging supplier provides a DoC claiming “full FDA compliance” for food contact applications. When asked for migration test reports, the supplier cannot produce any testing documentation. Follow-up requests for lot-specific CoAs yield a generic product specification sheet dated four years ago with no lot references. Additional emails receive responses restating compliance claims without providing requested evidence. Decision: Fail. Rationale: Cannot establish that test evidence exists; cannot link claims to current production; supplier is non-responsive to specific documentation requests.

How to Document the Audit So It Survives a Health Inspection or Internal Review

Audit defensibility comes from organized evidence and a short rationale that ties scope and traceability to the decision. A defensible audit exists in writing. If your compliance rationale lives only in email threads and memory, it will not survive scrutiny when inspectors, auditors, or your own management ask how you verified supplier compliance.

Build a Compliance Binder Structure

Whether physical folders or digital file systems, the structure should enable rapid retrieval of all relevant documentation during inspections or reviews.

Folder 1 — Supplier Identity: Legal entity, site information, product list, and key contacts.

Folder 2 — Compliance Packet (per product grade): Scope statement or assurance letter, test reports where applicable, and a one-page restrictions and intended use summary.

Folder 3 — Traceability Artifacts: Lot or batch coding explanation, example labels or photos if available, and shipment documents showing how lots are captured.

Folder 4 — Decisions: One-page decision record containing Pass/Fail/Needs Clarification outcome plus rationale, reviewer name, date, and renewal trigger.

Establish Naming Conventions

A consistent format allows quick retrieval during time-pressured situations. Use a pattern such as SupplierName_ProductGrade_DocumentType_Version_Date. For example: AcmePaper_KraftLiner300_DoC_v3_2026-01-10.

Set Renewal Cadence

Establish appropriate review frequency based on your risk profile.

Time-based: Annual review represents a reasonable baseline for active suppliers to confirm documents remain current.

Change-based: Immediate review should occur upon notification of formulation or process changes from the supplier, upon changes in regulatory requirements affecting your target markets, or before contract renewal or significant volume increases.

When an inspector or internal auditor asks how you verify your packaging suppliers, your answer is the binder. The workflow you followed is documented. The evidence you relied on is filed. The decision rationale is written. This documentation separates defensible compliance from hopeful compliance—the difference between “we verified” and “we assumed.”

For Suppliers: How to Prepare a Buyer-Ready Compliance Packet (Without Overclaiming)

Suppliers win audits faster by presenting scoped, coherent evidence that maps to lots—while avoiding blanket claims. Buyers following structured audit workflows will request specific documentation. Suppliers who provide clear, complete, and traceable evidence reduce friction and accelerate qualification — list your company free to connect with buyers seeking compliant partners.

What Buyers Want (and Why)

A scoped statement of intended use reduces ambiguity. Evidence that is internally consistent reduces review cycles. A clear mapping from evidence to lots and shipments reduces professional risk for the buyer.

Buyer-Ready Packet Checklist

One-page scope statement: Include exact grade, composition boundaries, intended use conditions, and restrictions. State the regulatory frameworks you comply with and the use conditions your testing covers. Avoid vague “food-safe” claims that provide no actionable information. Specify the food types your testing addresses, the temperature ranges covered, and the contact duration validated.

Supporting evidence: Provide assurance documentation with clear scope, regulatory basis references, and test scope with article identification that matches the grade. Include migration test reports with complete parameters—the simulant used, time and temperature conditions, the laboratory name, test date, and the specific limits tested against. If your testing covers multiple food types or conditions, organize the data clearly with separate sections or summary tables.

Lot-traceable Certificates of Analysis: Every production lot should have an associated CoA with clear lot identification. Design your documentation so buyers can easily match CoA lot numbers to their incoming shipment documentation. If your CoAs reference internal batch codes, provide clear mapping to the lot numbers appearing on shipping documents and product labels.

Composition disclosure: For paper-based packaging, identify fiber sources, coatings, adhesives, and inks. If any component has its own compliance documentation from upstream suppliers, include it in your packet or clearly indicate how buyers can request it. Proactive disclosure builds trust; reactive disclosure after buyer questions suggests reluctance.

Traceability addendum: Explain where lot codes appear, how lots map to shipments, and how customers can connect lot numbers to their purchase orders. This addresses one of buyers’ primary verification requirements.

Change-control statement: Provide a documented commitment that buyers will be informed of any formulation changes affecting compliance status before those changes affect shipped products. This commitment differentiates suppliers with mature compliance systems from those managing compliance reactively.

Language to Avoid (Overclaiming Risk)

Do not state “FDA approved”—FDA does not approve food-contact materials; it permits substances under specific conditions. Do not state “FDA certified”—this phrasing suggests a formal certification process that does not exist. Do not claim “compliant for all food applications” or “guaranteed compliant everywhere” or “safe for all foods” unless your testing genuinely covers all food types and all relevant conditions, which is rarely the case for any single material.

Language That Helps (Clear and Auditable)

“Evaluated for the following intended conditions of use…” provides clear scope. “Applies to the following grade(s) and composition range(s)…” defines boundaries. “Lot identification and mapping method is as follows…” addresses traceability directly.

Specific, accurate claims supported by traceable evidence are more credible—and more useful to buyers—than broad claims supported by nothing verifiable.

Building Your Compliance Shield

The Compliance Shield is not a single document or a one-time check. It is a repeatable method: define your use conditions, request the evidence stack, verify what the documents actually prove, match test conditions to your application, enforce the traceability chain from document to lot to shipment, and make a defensible decision. Then document everything.

Certificates show that testing happened somewhere, at some time, under some conditions. The audit workflow shows whether that testing actually protects your specific application. The difference matters when inspectors arrive, when internal audits occur, or when a quality issue surfaces and you need to demonstrate that your supplier verification was thorough rather than superficial.

The next time a supplier file crosses your desk, you now have the framework to move beyond “looks complete” toward “verified and traceable.” That shift—from passive acceptance to active verification—distinguishes compliance programs that survive scrutiny from those that merely hope for the best.

The certificate-only approach that trapped the buyer in this article’s opening is not inevitable. It is a choice—one you can now replace with evidence-based verification.

Ready to connect with packaging suppliers you can verify?

Find packaging suppliers on PaperIndex to connect directly with manufacturers and exporters across a vast global network. Once you identify potential partners, apply the Compliance Shield workflow to request and validate their evidence stack before making sourcing decisions.

Need quotes for a specific requirement? Submit your buying requirements and build documentation requests into your RFQ from the start.

Disclaimer:

This article provides general educational information about auditing food-contact packaging suppliers. Requirements can vary based on material type, coatings/inks/adhesives, intended food contact conditions, and jurisdiction. For organization-specific decisions, consult qualified compliance professionals.

Our Editorial Process:

Our expert team uses AI tools to help organize and structure our initial drafts. Every piece is then extensively rewritten, fact-checked, and enriched with first-hand insights and experiences by expert humans on our Insights Team to ensure accuracy and clarity.

About the PaperIndex Insights Team:

The PaperIndex Insights Team is our dedicated engine for synthesizing complex topics into clear, helpful guides. While our content is thoroughly reviewed for clarity and accuracy, it is for informational purposes and should not replace professional advice.