📌 Key Takeaways

Choosing recycled or virgin paper for food packaging depends on what touches food, how hot and greasy the food is, and whether you can prove safety with matching test reports.

- Match Fiber to Food Contact: Recycled paper works for outer boxes that never touch food, but hot or greasy items touching paper directly usually need virgin fiber or a tested barrier layer.

- Certificates Expire When Things Change: Safety tests from the original recipe might not match what you’re getting now if suppliers quietly changed factories, ingredients, or processes.

- Test Conditions Must Match Real Use: A test done at room temperature with water tells you nothing about pizza boxes holding hot, oily food for thirty minutes.

- Barriers Need Proof, Not Promises: A coating only counts as a “functional barrier” if testing shows it actually blocks the specific chemicals under your actual serving conditions.

- Build an Audit-Ready Folder: Keep current compliance certificates, test reports matching your use cases, and dated supplier confirmations that formulas haven’t changed.

Proof that matches reality beats claims that sound good on paper.

Procurement managers and food-service operators balancing sustainability goals with safety requirements will find a clear decision framework here, preparing them for the detailed guidance that follows.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Marketing is pushing for eco-friendly packaging. Operations are worried about contamination complaints. And somewhere between those two priorities, you’re staring at supplier certificates wondering whether ‘food safe’ actually means anything when a health inspector shows up asking for migration test reports.

This tension between sustainability goals and food safety requirements is legitimate. Recycled fiber can carry chemical residues from its previous life as newspapers, printed cartons, and adhesive-coated packaging. Virgin pulp starts cleaner but still requires verification. The choice isn’t about which fiber is “good” or “bad” — it’s about matching fiber type to your specific use conditions and having documentation that proves safety under those conditions.

Understanding migration risk mechanics and building a systematic approach to fiber selection moves you from anxious guessing to confident, documented decisions that hold up during audits.

When Recycled Fiber Is Higher Risk (and When It’s Not)

Recycled fiber presents higher migration risk when food packaging paper directly contacts fatty or hot foods without a functional barrier between the recycled layer and the food. The concern centers on mineral oil hydrocarbons and other contaminants that accumulate in recovered paper streams.

For secondary packaging—outer shipping boxes, display sleeves, cartons that never touch food directly—recycled fiber generally presents acceptable risk, provided the primary food packaging paper serves as an effective barrier against volatile substances. Note that physical separation alone may not prevent the migration of volatile mineral oils (MOSH/MOAH) through standard plastic or paper inner bags; a functional barrier is often required to ensure total safety.

The industry is trending toward a practical division: direct contact with fatty or hot foods generally calls for virgin fiber or a validated barrier structure, while secondary and outer packaging can often accommodate recycled content with appropriate documentation. This isn’t a rigid rule but reflects how risk, sustainability, and verification capabilities intersect for most food-service operations.

What “Migration Risk” Means in Food Packaging Paper

Migration is the movement of chemicals from food packaging materials into food over time. The pathway runs from residues in recovered paper or printing and converting processes, to the food-contact surface, and finally into the food itself. Three factors drive how much transfers and how fast: food composition, temperature, and contact duration.

Two technical terms appear frequently in migration discussions. Set-off refers to the transfer of printing-ink components from a printed surface to a food-contact surface during stacking or winding — a concern because food packaging often sits in warehouses for weeks before use, giving set-off plenty of time to occur. NIAS (non-intentionally added substances) describes impurities, by-products, and breakdown products that may be present even when not deliberately added. Both concepts matter because contamination can arrive through routes you didn’t specify or control.

Consider the difference between a dry bakery box holding croissants for two hours versus a greasy wrapper holding hot fries for thirty minutes. The croissants sit in dry, room-temperature contact — minimal extraction. The fries combine fat (which pulls oil-soluble compounds from paper), heat (which accelerates molecular movement), and direct surface contact—conditions where Kit level ratings become critical for grease barrier performance. Same food packaging material, vastly different migration profiles.

Major regulatory frameworks establish the principle that food-contact materials must be sufficiently inert under intended use conditions. Major regulatory frameworks establish the principle that food-contact materials must be sufficiently inert under intended use conditions. The EU Framework Regulation (EC) No 1935/2004 and U.S. FDA regulations (specifically the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and sections including 21 CFR 176.170 and 176.180) require that food packaging paper shouldn’t transfer substances to food in quantities that could endanger health or unacceptably change composition. The specific limits and testing requirements vary by jurisdiction — always validate requirements for your target markets.

Contaminant Profiles in Secondary Fiber Streams

The risk with recycled fiber isn’t that recycled material is inherently inferior. The risk is that inputs and processing history are harder to control.

Recovered paper streams contain materials from countless sources: newspapers printed with mineral oil-based inks, cardboard with hot-melt adhesive residues, office paper with toner particles, food packaging with previous coatings and treatments. De-inking processes — where recovered paper is treated to remove printing inks and other contaminants — reduce but don’t eliminate this chemical history.

The European Food Safety Authority’s risk assessment of mineral oil hydrocarbons identifies two compound categories of concern. MOSH (mineral oil saturated hydrocarbons) accumulate in human tissue. MOAH (mineral oil aromatic hydrocarbons) include compounds with potential carcinogenic properties. Both can migrate from recycled paperboard into food, particularly dry foods stored for extended periods. The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) has communicated that packaging — including recycled cardboard — can be a source of some mineral oil residues discussed in relation to EFSA’s assessment.

Virgin fiber producers control inputs from forest to finished pulp. A recycled fiber processor works with whatever the waste stream delivers, and that stream changes daily. Even with quality controls, batch-to-batch variability in recycled content is inherently higher than in virgin production.

Why Virgin Pulp Isn’t “Automatically Safe” Either

Virgin fiber provides a cleaner starting point, not guaranteed safety. The finished food packaging paper still contains additives that could potentially migrate: sizing agents that control ink absorption, wet-strength resins that maintain integrity when wet, coatings that provide grease resistance or moisture barriers.

The BfR Recommendation XXXVI provides detailed requirements for paper and board in food contact applications, covering both virgin and recycled materials. Components must be evaluated. Testing must match intended use conditions. Documentation must demonstrate compliance.

Virgin pulp’s advantage is traceability and consistency — you can verify what went into the material and expect similar composition batch to batch. That’s valuable, but it doesn’t eliminate the need for Declarations of Conformity (DoC) and supporting migration test reports.

Risk Matrix: Choose Fiber Type by Use Case

| Use Case | Food Type | Risk Drivers | Safer Default | Evidence to Request |

| Direct contact, no barrier | Dry goods (bakery, bread), short contact | Extended storage, set-off potential | Virgin pulp or controlled recycled (case-by-case with strong evidence) | Declaration of Conformity (DoC) + dry-simulant migration testing |

| Direct contact, no barrier | Fatty/oily foods | Fat extraction accelerates migration | Virgin pulp | DoC + fatty-simulant testing |

| Direct contact, no barrier | Hot-hold items (≥60°C / 140°F) | Heat + fat combination | Virgin pulp | DoC + elevated-temperature testing |

| Direct contact, extended hold | Extended time and/or warmth | Prolonged exposure increases transfer | Virgin pulp or recycled with verified barrier | DoC + time/temp-realistic testing |

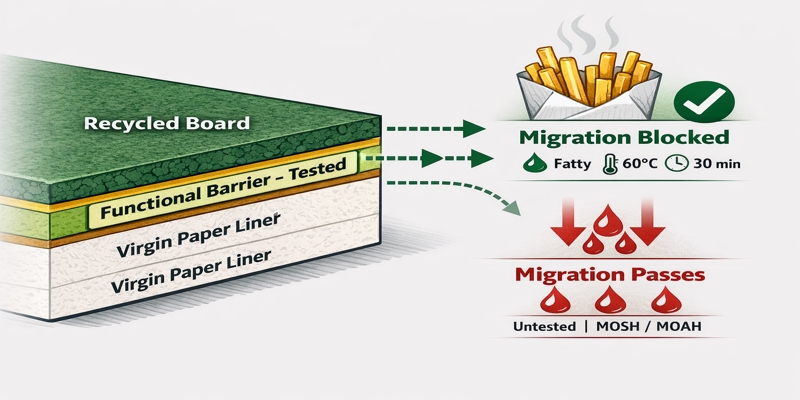

| Direct contact with functional barrier | Any food type | Barrier integrity critical | Recycled + validated barrier | DoC for all layers + barrier performance data |

| Secondary packaging only | Any (food in primary pack) | Volatile migration risk | Recycled acceptable | Requires verification that primary packaging acts as a functional barrier against mineral oils |

While virgin pulp excels at minimizing contamination variables, recycled with a validated functional barrier can be superior when sustainability certification is a priority and you can verify barrier performance. The right choice depends on your specific risk tolerance, sustainability commitments, and verification capabilities.

Mitigations That Move the Needle

Several approaches can reduce migration risk when sustainability goals favor recycled content.

Functional barrier layers create physical separation between recycled fiber and food. Research from the Fraunhofer IVV on mineral oil barriers demonstrates that properly designed barriers significantly reduce MOSH/MOAH transfer. “Functional barrier” is a performance claim requiring testing verification — a layer that reduces specific contaminants under specific conditions, not a marketing term. Barrier performance must be validated against the specific thermal and chemical profile of the end product; ambient testing provides no assurance for high-temperature fatty food contact.

Virgin fiber liners on food-contact surfaces allow recycled content in outer layers. The food touches only virgin material while the structure benefits from recycled fiber’s environmental profile.

Controlled feedstocks limit recycled inputs to food-grade recovered paper rather than mixed post-consumer waste. This reduces variability but limits availability and increases cost.

Low-migration inks and adhesives in the broader paper stream reduce contamination burden over time. This benefits the entire recycled paper ecosystem but isn’t something you control directly — it’s an industry-level improvement.

None of these mitigations work on promises alone. Each requires documentation demonstrating performance under conditions matching your actual use—the same principle behind verifying compliance beyond certificates..

What to Ask Your Supplier: A 10-Question Migration Evidence Checklist

This checklist works for procurement teams evaluating food packaging paper suppliers and for suppliers preparing evidence packages that accelerate food packaging paper buyer approvals.

- Does your Declaration of Conformity specifically name this product grade and format?

- Which regulatory frameworks does documentation reference — EU, FDA, other?

- What food types are covered (dry, aqueous, fatty)?

- What time and temperature conditions are covered, including hot-hold scenarios?

- What migration testing was performed, and what food simulant was used?

- If recycled content is present, what feedstock controls exist, and does testing address MOSH/MOAH specifically?

- If printed, coated, or laminated: what evidence covers inks, adhesives, and coatings?

- How do you address non-intentionally added substances (NIAS) — screening approach or rationale?

- What batch and lot traceability exists from raw materials through finished product?

- What formulation or process changes trigger re-testing, and what is the change-control process?

Building robust supplier verification workflows helps catch compliance drift before audits do.

For suppliers reading this: proactively preparing this evidence package removes friction from buyer qualification processes. A DoC with test reports matching common use conditions (room temperature dry, warm fatty, hot hold) covers most food-service applications. For detailed guidance on navigating specific migration limits and test conditions, the testing parameters matter enormously.

Common Failure Modes During Health Inspections and Audits

Consider a scenario where an auditor reviews your packaging documentation binder. She’s looking for evidence that your takeout containers are safe for hot, greasy food. You hand her a certificate. It says “food grade.” She looks up and asks what temperature and fat level the testing covered. You don’t know.

Three documentation gaps cause most audit problems.

Generic claims without scope. A certificate stating “food safe” or “compliant” without specifying which foods, temperatures, and contact durations proves nothing about your specific application. This pattern is so common that we’ve written extensively about why “food safe” is a meaningless label and what to ask instead.

Test conditions that don’t match actual use. Migration testing performed at 20°C for 10 days with an aqueous simulant tells you nothing about pizza boxes holding hot, oily food for 30 minutes. Auditors increasingly check whether test parameters align with real-world use.

No change control or traceability. Suppliers reformulate products, switch raw material sources, and modify processes. Without notification and re-testing protocols, you can’t know whether last year’s compliance documentation still applies to this year’s shipments.

Keep an audit-ready binder with current Declarations of Conformity, supporting test reports with conditions matching your use cases, and dated supplier confirmations that formulations haven’t changed. For a systematic approach to building supplier verification protocols, structured documentation prevents scrambling when inspectors arrive.

Decision Tree: Recycled vs. Virgin for Your Menu and Food Packaging Paper Format

Step 1: Does packaging paper directly contact food?

- If not, recycled fiber is generally acceptable. Request basic compliance documentation plus set-off and printing controls if relevant. Stop here.

- Yes → Continue to Step 2.

Step 2: For direct contact, Identify the food type?

- Dry foods (bakery, crackers, dry snacks) → Go to Step 3A.

- Fatty, oily, or hot foods → Go to Step 3B.

Step 3A: Dry food contact — what is the contact duration?

- Short contact, controlled conditions → Recycled may work case-by-case with strong evidence.

- Extended storage or warmth → Virgin pulp recommended, or recycled with verified barriers.

- Evidence packet: DoC + migration testing with dry simulant matching storage duration.

Step 3B: Fatty or hot food contact — is there a validated functional barrier?

- Yes, with barrier testing under fatty/hot conditions → Recycled with a barrier may work.

- No barrier → Virgin pulp strongly recommended.

- Evidence packet: DoC + migration testing with fatty simulant at elevated temperature matching actual hold conditions.

Minimum evidence for any direct-contact application:

- Declaration of Conformity naming specific product

- Migration test reports with conditions matching your use

- Component evidence covering inks, adhesives, and coatings if applicable

- Batch traceability documentation

- Change notification protocols

Frequently Asked Questions

Is recycled paper safe for food contact?

It depends entirely on application. Recycled paper can be safe with functional barriers, controlled feedstocks, and validated testing. For direct contact with fatty or hot foods without barriers, it presents higher risk than virgin alternatives. For secondary packaging with no food contact, recycled content is typically acceptable.

What are MOSH and MOAH?

Mineral oil saturated hydrocarbons (MOSH) and mineral oil aromatic hydrocarbons (MOAH), these contaminants, originating from newspaper and offset inks, are categorized by their molecular structure and toxicological impact. MOSH accumulates in tissue; MOAH includes potentially carcinogenic compounds. Both can migrate into food under certain conditions.

Do coatings stop migration?

Not all coatings function as migration barriers. Moisture-resistant coatings may do nothing against mineral oil transfer—a common misconception similar to the wax paper trap where generic wraps fail under high-heat conditions. Performance varies by chemistry, structure, and exposure conditions. “Functional barrier” means a layer tested and verified to reduce specific contaminants under specific conditions — not simply any coating.

What is a functional barrier?

A layer or structure designed and verified to prevent or significantly reduce migration of specific substances from outer layers to food under defined conditions. Verification requires testing demonstrating reduced migration compared to unbarriered materials under conditions representing actual use.

Can compostable coatings serve as barriers?

Some can, some cannot. Compostability describes end-of-life behavior, not barrier performance. A compostable coating might or might not block mineral oil migration — the only way to know is through testing under relevant conditions. Don’t assume environmental credentials translate to food safety performance.

For buyers planning an eco-friendly packaging transition, the path forward combines fiber selection with verification. Start with your highest-risk applications (hot, fatty, direct contact), establish evidence requirements, then work toward sustainable options that meet those requirements.

For food-grade certification standards and what documentation actually proves, understanding certificate limitations helps evaluate supplier claims critically.

When you’re ready to identify suppliers who can provide proper documentation, you can explore food packaging paper mills, browse food packaging paper suppliers, or submit an RFQ to receive quotes from verified sources.

Disclaimer:

This article is for informational purposes and does not constitute legal, regulatory, or professional advice. Requirements can vary by market and application.

Our Editorial Process:

Our expert team uses AI tools to help organize and structure our initial drafts. Every piece is then extensively rewritten, fact-checked, and enriched with first-hand insights and experiences by expert humans on our Insights Team to ensure accuracy and clarity.

About the PaperIndex Insights Team:

The PaperIndex Insights Team is our dedicated engine for synthesizing complex topics into clear, helpful guides. While our content is thoroughly reviewed for clarity and accuracy, it is for informational purposes and should not replace professional advice.